Ambleside Schools International Blog

Browse more Ambleside Schools International Resources.

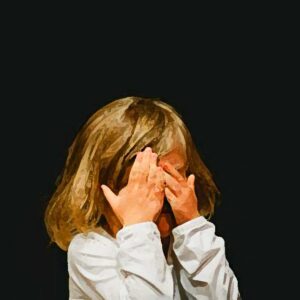

Bringing Up Children in Distressing Times - Part 1

These last weeks have been taxing. Routines have been radically altered. Freedoms have been constrained. Normal pleasures have been curtailed. For many, income has been disrupted. And perhaps most trying of all, the future is uncertain. The illusion that we are in control is being challenged. Such testing times can be stressful for parent and child alike.

In these exceptional times as in normal times, it must be remembered that every child is unique and responds to adversity uniquely. No two children do life quite the same way. No two are delighted in quite the same way. No two are distressed in quite the same way. Some are more skilled at responding to adversity, some less so; either way, there is always diversity. We see this diversity in the way children have responded to life under the threat of COVID-19. Many children, while they may be missing normal routines, outings, and community, are nonetheless at peace with the current home regime. Such children are responding with the same degree of blessedness and sinfulness as they would in “normal” times. Other children seem not to be their “normal” selves. They may be excessively clingy or selfish, perhaps unusually prone to outbursts of tears or fits of anger. How is this to be understood? And, more importantly, what is to be done?

The Story of Suzie and the Principal

The school secretary rushed into the principal’s office and exclaimed, “The kindergarten needs your help!” Up from his desk, through the door, and down the stairs went the principal. As he approached the door of the kindergarten classroom, a piercing shriek could be heard resounding down the hall. Opening the door, the principal saw to his right, in the front of the classroom sitting on the carpet with their teacher, eleven students, all wide-eyed and slightly pale. To his left, in the back corner of the classroom stood Suzie, screaming at the top of her lungs. Immediately, the principal turned to the eleven students and calmly but clearly said, “Suzie has a very big sad, doesn’t she?” Every head nodded vigorously in agreement. “Have you ever had a very big sad?” Again, every head nodded. “It’s all going to be okay.” And eleven little bodies all released a sigh of relief.

Turning to the other side of the classroom, the principal said, “Suzie, how big is your sad? Is it this big?” holding his hands six inches apart. “This big?” holding his hands thirty inches apart. “Or this big?” stretching his hands as far apart as he could. Suzie, immediately thrust her hands as far apart as she could, all the while screaming at full throttle. “Oh, that’s hard, let me know when it’s only this big,” said the principal holding his hands thirty inches apart. He then turned to the teacher and instructed her to continue reading.

Thus, the teacher read, eleven students peacefully attended to the story, Suzie continued to scream though not quite so vigorously, and three minutes passed. The principal asked again calmly, looking deeply, inquisitively into her eyes, “Suzie, how big is your sad now? Is it this big? This big? Or this big?” Again, Suzie thrust her hands as far apart as she could, all the while continuing to scream. “Okay, let me know when it’s only this big,” said the principal holding his hands thirty inches apart. Another three minutes passed, and the principal asked again, “Suzie, how big is your sad now? Is it this big? This big? Or this big?” This time Suzie responded with something between a whine and a scream, holding her hands twenty inches apart. “Good,” said the principal, “let me know when it’s only this big,” holding his hands six inches apart. A few minutes later, the teacher finished the story, and the class got up to go outside. The principal indicated he would remain with Suzie. As the class departed, Suzie became increasingly quiet. The principal then asked a final time, “Suzie, how big is your sad?” This time she held her hands six inches apart. “Good, come sit beside me,” said the principal, and the following conversation ensued.

“That was a very big sad, wasn’t it?”

Suzie vigorously nods her head, yes.

“Do big sads sometimes just come and jump on you like that?”

Again, a vigorous nod.

“Tell me, Suzie, do you know when a big sad is coming? Can you feel it?”

Again, a nod.

“When a big sad is coming, where does it start? Does it start in your stomach, your heart, your head or some other part of your body?”

“My stomach.”

“And it spreads from there so that you don’t know what to do and can only scream?”

Again, a nod.

“There is a way to stop the spread of the big sad.”

“How?”

“You’ve been learning your numbers, right? Can you count to 100?”

“Yes.”

“Show me.”

Suzie counts from 1 to 50.

“Whoa! You know your numbers, Suzie! Now, the best way to fight the big sad, when it starts to grow, is to redirect your thinking to something else. Why don’t you try it? Next time you feel a big sad coming, instead of thinking about the big sad, think about your numbers and start counting. See how far you can count before the big sad is chased away. Are you ready to go and rejoin you class?”

“Yes,” she said.

Suzie and the principal walked hand in hand to join the class. As Suzie did so, she was all smiles, and for the remainder of the day, she was peaceful. The next day during lunch, Suzie’s teacher approached the principal, saying, “The strangest thing just happened. This morning, Suzie got that look in her eye, and I said to myself, ‘Oh no, here we go.’ But then, I heard her whispering, ‘One, two, three, four, five’ and so on. And the clouds passed without a storm.”

Before exploring the lessons to be learned, a little of the backstory would be helpful. Suzie’s teacher had instructed her students to move from their desks to the carpet for the reading of a story. Suzie asked to sit next to her teacher. As Suzie had sat beside the teacher the day before, her teacher graciously declined the request. Lacking the emotional-relational maturity to handle this disappointment well, Suzie rapidly decompensated and was soon screaming at the top of her lungs from the other side of the classroom.

Like every human person, Suzie is made for and seeks beatitude, relational blessedness. More than sensual pleasure, relational blessedness is the internal state of fruitful joy and peace, that manifests itself to the world. It is nurtured and sustained by the fruitful, joy/peace of one’s people, and ultimately by the fruitful, joy/peace of God. Sin and the “groanings”[1] of a broken world often disrupt joy/peace. When joy/peace is disrupted the human brain begins a faster than consciousness search of memory,[2] looking for a mental map that would guide back to joy/peace. While a psychologically and spiritually mature person will have many maps back to joy/peace, an immature person will have few. When a distressing event occurs and one lacks a mental map back to joy/peace, the brain reacts as if in a feverish loop, running round and round in circles, seeking an answer it simply does not have. Frontal lobes begin to darken. Executive function becomes unhinged, and the brain regresses to fight, flight, freeze or cling mode.[3] If we have been paying attention, we all will have noticed this in our children, our co-workers, our friends, our spouse, and even ourselves. A distressing event occurs, and a person ceases to be his or her usual self. There is a desperate, out of control look in the eye. Behaviors become erratic, unreasonable, angry, anxious, depressed and/or enmeshed. The mind’s elevator is no longer getting to the top floor. This is all quite normal, a common phenomenon in a fallen world. We need not become overly fretful. The question is, how are we to be helpful?

While the story of Suzie and the principal is taken from a particular school situation, it provides lessons for coming to the aid of distressed brains at home or in the classroom.

Lessons to Be Learned

1. Remain at peace when walking into a highly charged situation. This is essential. One cannot be part of the solution if one becomes part of the problem. One cannot bring peace if caught up in the distress. We can catch a distressed brain state like the flu (or COVID-19, for that matter). When two or more share a distressed brain state, they tend to spin out, getting farther and farther from joy/peace. It is quite impossible for one who is in a distressed brain state to help another recover from a distressed brain state. Parents and teachers are called to be the “bigger brains.” This can be difficult, and there are times when one must take a personal time out or tag team with someone not in distress state. In order to get back to joy/peace before attempting to come to a child’s aid; we must take seriously Jesus’ words, “Do not let your hearts be troubled.”[4]

2. Reset the emotional-relational atmosphere. Stress was in the air. The intensity was palpable. It could be seen on the faces of the other children. A distressed atmosphere amplifies distress, making it more difficult to get back to joy/peace. The principal resets the atmosphere by reassuring the other students. “Suzie has a very big sad, doesn’t she?” “Have you ever had a very big sad?” “It’s all going to be okay.” Most importantly, all the principal’s nonverbal communication—facial expressions, posture, voice tone, are reinforced by the statement, “It’s all going to be okay.”

3. Attune without becoming enmeshed. Looking intently into Suzie’s face, the principal’s face communicates concern but not distress. He understands her. He recognizes something is happening inside Suzie that is emotionally overwhelming to her, but not to him. He feels Suzie’s distress but can peacefully handle it. This stance is reinforced by the untroubled question, “How big is your sad?When it comes to attuning with a distressed brain, there are two failings. The first is to stay coldly aloof. It is a failure to empathize, to allow oneself to be connect with what the distressed person is feeling. The second is to become enmeshed. An enmeshed brain goes beyond empathy to “unreasonable pity” and, thereby, unintentionally amplifies the distressed brain’s feelings. The coldly aloof and the enmeshed are equally incapable of aiding a distressed brain in getting back to joy/peace.

4. Honor what comes from a distressed person’s voice but do not take it too seriously. While distressed brains desperately seek to communicate their internal reality, they cannot assess external reality very well. Suzie screams as if something terrible is happening. Objectively, this is simply not the case. But trying to convince Suzie that things really are not so bad and that she really ought not be responding in this way, would be of no help at all. Further, such talk would be to Suzie a denial of what she is experiencing. By asking, “How big is your sad?” the principal honored Suzie’s experience without buying into it. Always remember that a distressed brain has a remarkable capacity to fabricate a story for explaining to itself both its distress and its response to the distress. The story may appear ludicrous to the observer, but to the distressed brain it is absolute truth. One should never debate with a person in a distressed brain state. The reasoning part of his/her brain is simply not working. Wait until the brain gets back to joy/peace when the brain’s executive functions turn back on. Then and only then is there the possibility of a reasonable conversation. Forced attempts at “rational” conversation with a distressed little brain are usually vain attempts on the part of an increasingly distressed bigger brain to maintain control.[5]

5. Give hope. The greater a brain’s distress, the greater the sense of despair. Perhaps the distressed brain’s biggest fear is that the distress will go on and on and on, that it will never come to an end, eventually turning into a black hole which consumes the soul. The principal’s repeated admonition, “Let me know when it’s only this big,” communicates confidence that the distress will pass. It will not go on and on. There is the expectation of a return to joy/peace.

6. Give relational time. The return of a brain to joy/peace is a process that can be supported but cannot be controlled. Recovery takes time, sometimes more, sometimes less. It is absolutely necessary to give the needed time. One caveat: if a child is using personal distress as a manipulative tool to gain attention or to win a power struggle, it cannot be allowed to work. Most of the time in such cases, the child should be left alone, with the standing offer to return to life together, once he has “quieted his heart.”

7. Do not force it but do take advantage of a teachable moment. When a person is in the midst of a distressed brain state, it is not a teachable moment. Distressed brains are incapable of receiving verbal instruction well, and it is counterproductive to force the matter. However, if one has successfully aided a distressed brain in getting back to joy/peace, it becomes a very teachable moment. The principal took advantage of this moment to show Suzie that she is loved (sitting beside her, walking with her to rejoin the class, holding her hand) and to instruct her in a strategy for avoiding “big sads” in the future.

8. Change is almost never an instantaneous and complete reversal. Change usually occurs in frequency over time. This was not Suzie’s last “big sad. ”But it was the beginning of a process by which over time Suzie’s “big sads” became fewer and of less intensity; such that two years later, by the time Suzie was in the second grade, “big sads” were largely a thing of the past.

Final Thoughts

The school classroom is the setting for the story of Suzie and the principal; nonetheless all of the ideas explored here apply as much to home life as they do to the school. Principals, teachers, and parents alike will encounter distressed “little brains.” It is all quite normal. We are not just born sinners; we are also born emotionally-relationally immature. Thus, bringing distressed “little brains” to greater maturity is part of the job description of parents and teachers. We must acknowledge that it is not always easy. It is challenging to remain the peaceful, engaged “bigger brain” which is helpful to the little ones we love. Thus, the distress becomes an opportunity for growth not just for the “little brain” but the “bigger brain” as well.

The story of the principal and Suzie was primarily about recovery from a distressed brain state, but this is only half of the work to be accomplished. It is also the responsibility of parents and teachers to build resilience, the capacity to absorb adversity without slipping into a dysfunctional, distressed brain state. Building Resilience will be the topic of

Part II “Bringing up” Children in Distressing Times.

[1] Romans 8:19-23 (NRSV)

[2] Our brain’s search for a mental map back to joy/peace happens so rapidly, that we are not consciously aware of it.

[3] Much of addiction seems to be a form of clinging. A distressed brain, without a map back to joy/peace and lacking a person upon whom to cling, may substitute food, drink, pornography, or videogames.

[4] John 14:1 (NRSV)

[5] Note: A distressed brain also does not remember well. A distressed brain may make an outlandish claim or engage in outlandish behavior and later deny it completely. Assuming the child is normally honest, the now calm brain is probably not actively lying but simply has no memory of what was said or done. The brain was not functioning well, and the event was not recorded in memory. Because what was said and done is now rather incriminating, it is reflexively denied. Rather than denial, children should learn to respond by professing no memory of such words or deeds.

*Image courtesy of Caleb Woods all rights reserved. Creative Commons.