Ambleside Schools International Articles

Browse more Ambleside Schools International Resources.

Instructing in the Beauty Sense

Let’s consider together the Beauty Sense, a formative force rarely considered in its potent ability to shape the character of children. The Beautiful, together with the Good and the True, are servants to one another, each drawing to the others as it draws us to itself.

Charlotte Mason speaks of imagination with the trained eye and ear as central to the perception of beauty.

He must needs have Imagination with him to travel there, but still more must he have that companion of the nice ear and eye, who enabled him to recognize music and beauty in words and their arrangement. The aesthetic Sense, in truth, holds the key of this palace of delights. There are few joys in life greater and more constant than our joy in Beauty, though it is almost impossible to put into words what Beauty consists in; color, form, proportion, harmony – these are some of its elements.1

These elements of Beauty speak of perfection — completeness — and are often spoken of with Truth and Goodness, forming a triad.

They have been called “transcendental” on the ground that everything which is is in some measure or manner subject to denomination as true or false, good or evil, beautiful or ugly. But they have also been assigned to special spheres of being or subject matter — the true to thought and logic, the good to action and morals, the beautiful to enjoyment and aesthetics.2

Humans are created for and called to the transcendent, to climb over or move beyond, to excel, surpass, and surmount. And when this does not happen, something has gone wrong. Bill St. Cyr calls it a malformation. The malformed soul does not delight in the good, beautiful, and true, but rather in the biting, brutal, and base. As educators we must ask how we rightly form the hearts and minds of students of all ages.

At Ambleside, we hold as a first principle that Education is the “Science of Relations,” that our hearts and minds, our affections and desires are formed by the relational world which surrounds us, be it books and things, family and friends, social media and pop culture, or trends and technology. Many years ago, an Ambleside parent said to me, “We are the sum total of the books we read, the ideas we entertain, and the people we befriend.”

In the cultivation of the beauty sense, books hold the same primacy of place that do art and music. Mason said that in order to have a richly-stored imagination we must read much.3

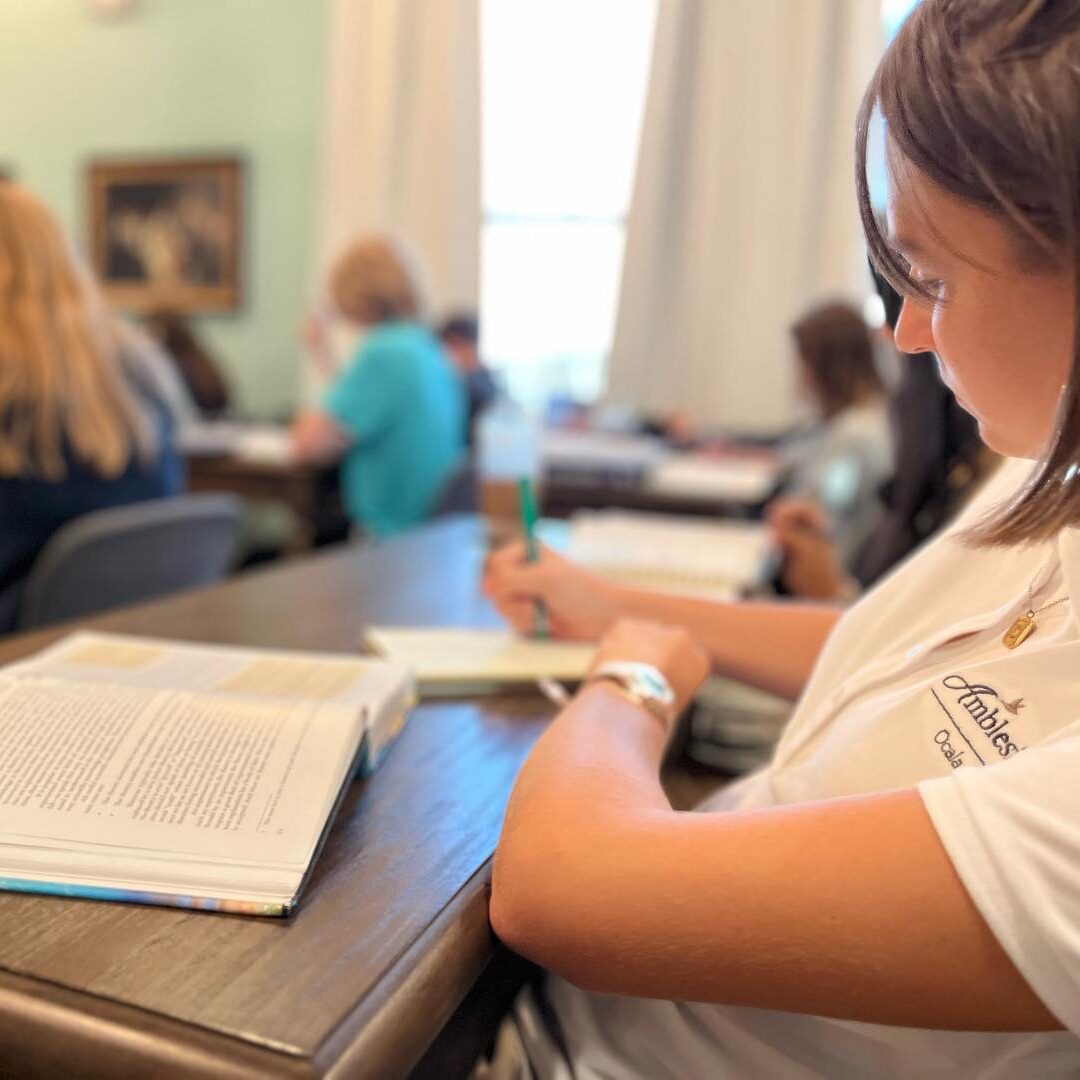

Students read thousands of pages a year in Ambleside Schools, beginning with a thousand plus pages in kindergarten read mostly by the teacher and culminating with eight to nine thousand pages each year of high school. They read books described as living, books filled with beautiful, vivid language, creating scenes for imagination, ideas of life, the knowledge of God and man, conduct and duty, a storehouse of thought wherein we may find all the great ideas that have moved the world.

Given the right book, cultivating the sense of Beauty, Goodness, and Truth begins with:

Expectation and Attention — “Everyday moments of epiphany are bestowed on everyone. Our role is to simply pay attention.”4

When opening a living book, a revelation, a manifestation of a new idea or truth awaits the reader. This truth can take the form of a clear, conscious thought or a yearning of the heart. One must participate in a careful reading of the text, assimilating its language, and responding to its ideas. We read to know, to know both mind and heart, to know in Goodness, in Truth, and in Beauty.

At Ambleside, a student cannot help but give his/her attention. At any given time in any given subject, the student will be called upon to read, narrate, or discuss. Throughout the day, living readings in fiction and non-fiction, citizenship, geography, history, Scripture, and science are thoughtfully engaged. Students are not left listless or passive. Each is engaged. Each experiences the reciprocity of giving and receiving insights from the author and from their classmates.

The manner by which a teacher cultivates the Beauty Sense is exemplified in an example from the 1845 autobiography, Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass. In this passage, twelve-year-old Douglass responds to a passage from The Columbian Orator.

In the same book, I met with one of Sheridan’s mighty speeches on and in behalf of Catholic emancipation. These were choice documents to me. I read them over and over again with unabated interest. They gave tongue to interesting thoughts of my own soul, which had frequently flashed through my mind, and died away for want of utterance. The moral which I gained from the dialogue was the power of truth over a conscience of even a slaveholder. What I got from Sheridan was a bold denunciation of slavery, and a powerful vindication of human rights. The reading of these documents enabled me to utter my thoughts, and to meet the arguments brought forward to sustain slavery; but while they relieved me of one difficulty, they brought on another even more painful than the one of which I was relieved. The more I read, the more I was led to abhor and detest my enslavers …

The idea as to how I might learn to write was suggested to me by being in Durgin and Bailey’s shipyard, and frequently seeing the ship carpenters, after hewing and getting a piece of timber ready for use, write on the timber the name of that part of the ship for which it was intended. When a piece of timber was intended for the larboard side, it would be marked thus — “L.” When a piece was for the starboard side, it would be marked thus — “S.”… I soon learned the names of these letters, and for what they were intended when placed upon a piece of timber in the shipyard. I immediately commenced copying them, and in a short time was able to make the four letters named. After that, when I met with any boy who I knew could write, I would tell him I could write as well as he. The next word would be, “I don’t believe you. Let me see you try it.” I would then make the letters I was so fortunate as to learn and ask him to beat that. In this way I got a good many lessons in writing, which is quite possible I should have never gotten in any other way. During this time, my copybook was the board fence, brick wall, and pavement; my pen and ink was a lump of chalk. With these, I learned mainly how to write. I then commenced and continuing copying the Italics in Webster’s Spelling Book, until I could make them all without looking on the book…. Thus, after a long tedious effort for years, I finally succeeded in learning how to write.5

After a short introduction regarding The Columbian Orator and the careful reading and narrating of the text, the teacher provided questions concerning Douglass’ response to his plight. Note that not all these questions would necessarily be discussed:

- Douglass is twelve during this time, and he is reading famous speeches. What effect does this have on his life? Why?

- The collection of orations includes such authors as: Socrates, Cicero, Jesus, Milton, William Pitt, Benjamin Franklin, George Washington, and native American chiefs. How do these readings act as a force in Douglass’ life?

- Wordsworth described the child as ‘father of the man.’ How did Douglass’ youth prepare him for manhood?

- Speak about the gifts of reading and writing and their importance in school and in life.

What one reads matters. The Beauty Sense is cultivated by encountering and sharing the beautiful in the lives of literary characters such as Frederick Douglass, a slave, and his quest for freedom.

Douglass instructs the human spirit through his story. We learn from his pages and his artistry in bringing to life what was imagined and remembered in his heart and mind. This book, and books like it, are living through their characters and conflicts, romps in the natural world with fawn and friend, through the earnest defiance of injustice to the human spirit, to the intimacy of family and friendship, challenges of loss and loneliness, hardships and slavery. Each chapter reflects and cultivates the transcendent triad of Beauty, Goodness, and Truth.

1 Mason, Charlotte. Ourselves. Wheaton, IL: Tyndale House Publishers, Inc., 1989. 41.

2 The Great Ideas, A Syntopicon of Great Books of the Western World. Adler, Mortimer Ed. William Benton Pub.,1990.

3 Mason, Charlotte. Ourselves. Wheaton, IL: Tyndale House Publishers, Inc., 1989. 50.

4 Schleske, Martin. The Sound of Life’s Unspeakable Beauty. Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing Co., 2020. xiii.

5 Douglas, Frederick. Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass. Tribecca Books. 45, 47-48