Ambleside Schools International Articles

Download a PDF version of this article.

Browse more Ambleside Schools International Resources.

Learning to Observe Truth

The following address was given at an art show and fundraiser for Ambleside School of Fredericksburg, Texas (a K-12 institution). Founded on the principles of British educator Charlotte Mason, Ambleside Schools International and its member schools believe a “living” education is influenced by 3 principles: atmosphere, discipline (habits), and life (living texts rich in ideas).1 Emily Bowyer is an alumna and current faculty member of the Fredericksburg school:

I would like to begin my brief remarks with a roll call, as it were, of some of the great masters of the artistic tradition: Fra Angelico, Pieter Bruegel, Winslow Homer, John James Audubon, Claude Monet and the Impressionists, Utagawa Hiroshige, Diego Velazquez, Georgia O’Keeffe, Rembrandt van Rijn, J.M.W. Turner, Leonardo da Vinci, Johannes Vermeer, Henri Matisse, Jacob Lawrence, and Vincent Van Gogh.

By the time Ambleside students begin high school, they will have spent three months with each of these artists, studying at least a dozen of their works with care and attention until they can happily hang each one in the gallery of their memories. We recognize, as Charlotte Mason once did, that

“the power of appreciating art and of producing to some extent an interpretation of what one sees is as universal as intelligence, imagination, [or] speech. . . But there must be some knowledge and, in the first place, not the technical knowledge of how to produce, but some reverent knowledge of what has been produced .”2

This is not to say that we neglect the technical side of our students’ art education. On the contrary, they are given weekly instruction in drawing or painting, and regularly produce free-hand color illustrations in science and history lesson books and watercolor entries in nature diaries. In addition, they complete several detailed reproductions of their favorite masterworks every year. Nonetheless, we discover that when we offer our students a relationship with the great artists of the past and present, they are more inspired to pursue excellence in their own artistic endeavors and to learn more about what it means to live, to be fully human.

Calvin Seerveld, an American art historian who studied in the Netherlands and then went on to a professorship in Canada, once wrote that

“art calls to our attention in capital, cursive letters. . .

what usually flits by in reality as fine print.”3

We must summon our aesthetic capacity—our innate power to appreciate art—to watch for these “capital, cursive letters,” and even to seek them out. In other words, we must learn to open our eyes. Why? Because otherwise we might miss an opportunity to see our lives with greater clarity, insight, and wisdom. Great works of art serve as parables, 4 not mere copies, of the human experience. They reveal hidden meanings by engaging our imagination and our inner eye, something that Helen Keller called “soul-sense, which sees, hears, feels, all in one.” 5

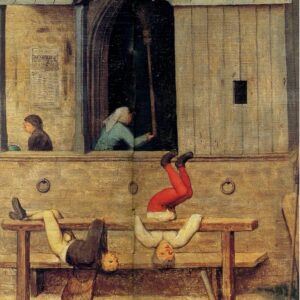

Allow me to demonstrate: Van Gogh teaches us about loneliness by painting an old chair with a pipe and tobacco on it, the owner of the chair, a cherished friend, made conspicuous by his total absence. Vermeer shows the virtue of a milkmaid going about her daily work with strength, vitality, and fortitude, reminding us that there is dignity even amidst the seemingly menial occupations. Matisse highlights the remarkable shapes and colors present in every person, place, and thing around us, whether it is as stationary as a French window, or as dynamic as the couple having a conversation beside it. Bruegel celebrates the ingenuity and rashness of children at play. Velazquez depicts a Venus looking in a mirror; her forlorn gaze tells us, “Beauty isn’t everything.” Monet transfixes us with the utter tranquility of a cluster of lilies floating on the surface of water. Turner exposes the travesty of the slave trade by depicting a single slave ship unburdening itself of unwanted human cargo during a storm. Da Vinci uncovers the scientific proportions of the human body in an ingenious way, while still preserving the enigmatic mystery of a woman’s smile.

These are but a very few examples of the way in which art serves to draw our attention to ideas that we too often ignore or forget. The poet Robert Browning put it thus:

“For, don’t you mark? we’re made so that we love

First when we see them painted, things we have passed

Perhaps a hundred times nor cared to see. . .”6

Why might this be the case? How can a painting, a sculpture or a drawing cause us to love that which we have overlooked so often in reality? I would venture to say that when we see something for the first time through the lens that an artwork provides, we see its essence. Art comes to us an invitation. It invites us to know the truth of a thing. Great artists are firstly great observers. They teach us how to clearly see the details, the symbols, the wonder of everything around us. The English poet Gerard Manley Hopkins called this the “inscape” 7 of all created matter, its inner glory. Artists possess the gift of turning the world inside out so that the invisible truth becomes visible. We are all created to yearn for this truth, and to love it when once we find it. There are times when a piece of art depicts something less than beautiful, even grotesque, but if it tells the story of the world’s brokenness or cruelty in a truthful way, it remains an important object of our study, if not our enjoyment. Art should provoke us on our ongoing search for the Truth, and our souls will remain unsatisfied until we meet that same Truth, face to face.

1 See www.amblesidefredericksburg.com

2 Mason, Charlotte. The Philosophy of Education, Vol. 6 (Wheaton: Tyndale House, 1989), 214.

3 Seerveld, Calvin. Rainbows For the Fallen World (Toronto: Toronto Tuppence Press, 1980), 27.

4 Rookmaaker, Hans. “Images of Man in Art,” L’Abri Fellowship, Lecture, www.labri-ideas-library.org.

5 Keller, Helen. The Story of My Life (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1904), 122.

6 Browning, Robert. “Fra Lippo Lippi,” in My Last Duchess and Other Poems, ed. Shane Weller (New York: Dover, 1993), 43.

7 Hopkins, Gerard Manley. “Poetry and Verse,” Hopkins: Poems and Prose, Everyman’s Library Pocket Poets ed. Peter Washington (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1995), 123.

Image: Pieter Bruegel, detail, Children’s Games, oil on canvas, Kunsthistorisches Museum, Public Domain