Ambleside Schools International Articles

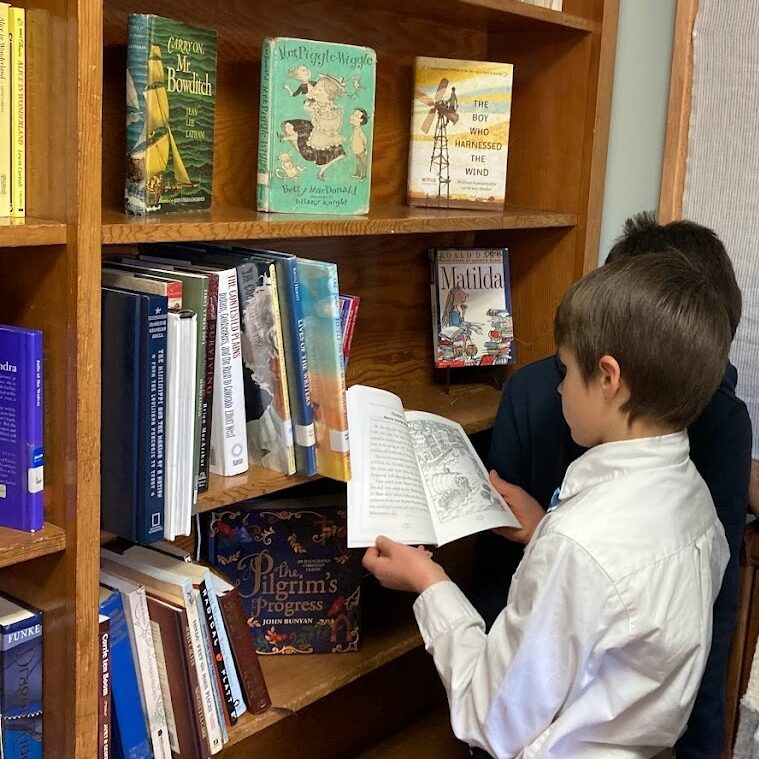

Image courtesy of Ambleside School of Ashland.

Browse more Ambleside Schools International Resources.

The Test of the Living Book

“One more thing is of vital importance; children must have books, living books; the best are not too good for them; anything less than the best is not good enough.”1

Don’t you admire the passion and conviction in Miss Mason’s voice when she argues that children are worthy of receiving the best books? Since they are born persons, there is no need for them to finish growing up before we give them beautiful literature; at six years old, entering kindergarten, they are already thoughtful and ready to learn about many things. Parents today encounter a modern problem when looking for living books, but the solution, which Miss Mason identifies for us, is ages-old, just the same as it’s always been.

The problem is that our society has become very good at producing books, stacks and stacks of them, often inexpensively. Authors mean well, but they are not always aware of their own “idea” of children, which is sometimes very low. You might find it sobering to hold a picture book and try to determine the author’s idea of children, for example: “Children want authors to talk exactly like little children,” or, “Children only care about familiar, everyday things,” or, we would hope, “Children need beauty and truth, and these are never wasted on them.”

How do we find stories by authors who think highly of children? How do we find a living book — a rare thing of life-giving power — amid many watery, bland stories; twaddle, as they used to say in Miss Mason’s time?

In her discussion of the “beauty sense” in her book Ourselves, Charlotte Mason gives us a way to test for true, living literature. The test is just as effective now as it was in her day. As you read it, watch for the following: what is it about the words in a text that makes a living book?

The thing is, to keep your eye upon words and wait to feel their force and beauty; and, when words are so fit that no other words can be put in their places, so few that none can be left out without spoiling the sense, and so fresh and musical that they delight you, then you may be sure that you are reading Literature, whether in prose or poetry. A great deal of delightful literature can be recognized only by this test.2

Pause and tell back to yourself: for what are you looking and waiting when you test literature?

Maybe you would like to try it. Take a moment to dwell, to wait on the words of both texts below: are the words powerful, beautiful, few, and delightful? Or are they many, but somehow lacking?

- There was once a witch who desired to know everything. But the wiser a witch is, the harder she knocks her head against the wall when she comes to it. Her name was Watho, and she had a wolf in her mind.3

- In a city called Stonetown, near a port called Stonetown Harbor, a boy named Reynie Muldoon was preparing to take an important test. It was the second test of the day — the first had been in an office across town.

If you are like me, the first text makes you want to cancel your obligations for the day and find out what happened to Watho. This is a living book. But the second one … perhaps you didn’t find it particularly interesting, but you wondered if it might turn interesting later. Would it be worth it to read more? I think the way we respond to that question depends on how much practice we’ve had. The more living books you find, the more precious they seem — you no longer want to spend time on stories that lack literary power. And that raises a question: how much of a chance should you give an unknown book, to let it prove its real nature to you?

Here is Miss Mason’s thought on that. She calls this thought “unhappy,” because sometimes children reject books we think are good for them. As you read, watch for how much you need to take in to decide whether you’re holding a living book or not; also listen for what happens in your mind once it’s declared the book to be living or twaddle:

A book may be long or short, old or new, easy or hard, written by a great man or a lesser man, and yet be the living book which finds its way to the mind of a young reader. The expert is not the person to choose; the children themselves are the experts in this case. A single page will elicit a verdict; but the unhappy thing is, this verdict is not betrayed; it is acted upon in the opening or closing of the door of the mind.4

How much text does she say you need to decide? And what happens to your mind once you have made the call?

You may have experienced this yourself: you pick up an old book, flip to a page halfway through, and accidentally read for an hour, immersed in another world — a living book! Or you take up a recommended book, but before the end of the first page, your mind wanders. You close the book, and it’s already fading — twaddle. You might feel obligated to keep the book, but it would be difficult to make yourself read and enjoy it, indeed. Children feel the same.

It takes a lot of digging, searching, trial and error, to keep on finding living books for your family, but it is a labor of “vital importance.” We modern people have blogs, lists, internet searches, and recommendations to give us ideas, but only the simple test of waiting for the force and beauty of words on a page will show whether you hold a treasure in your hands. Where will you discover your next living book?

Heidi Kimball

Associate Director of Curriculum, Training, and Homeschooling

1 Charlotte Mason, Parents and Children, p. 278

2 Charlotte Mason, Ourselves, p. 41

3 George MacDonald, The Day Boy and the Night Girl

4 Charlotte Mason, School Education, p. 228