Ambleside Schools International Articles

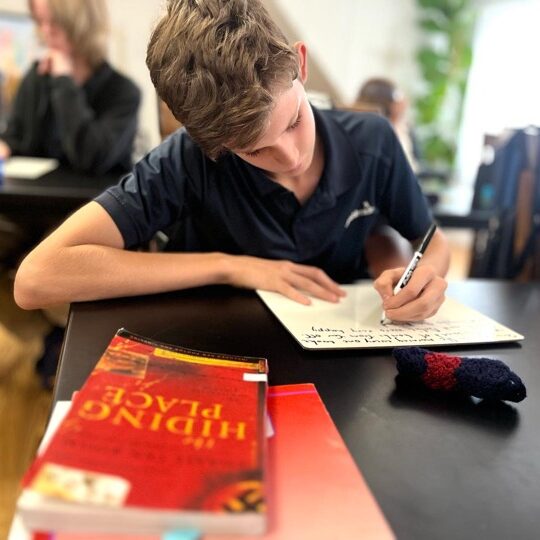

Image courtesy of Ambleside School of Ocala.

Browse more Ambleside Schools International Resources.

Video Series Part 11. Chapter Eight: Worthy Work

Worthy work is intrinsically satisfying. Students gain the satisfaction of knowing and of work well done. Well-intentioned adults may inadvertently contaminate the learning atmosphere by using artificial rewards and incentives, which demean the joy of knowing and diminish the student’s capacity for intrinsic motivation. Artificial incentives communicate to students that it is impossible to enjoy history, mathematics, science, and literature in and of themselves; they indicate to the student that “real life” is to be found in the incentives, such as the “Fun Friday” or other rewards. Ambleside teachers foster students’ affections for worthy work and the satisfaction and joy of learning.

In Part 11 of our video and discussion guides, Bill St. Cyr distinguishes the importance of calling a child up to worthy work and the detriment of its opposite.

Here are some excerpts from the Charlotte Mason volume Towards a Philosophy of Education that give some insight to the idea of work.

The Way of the Will. We may offer to children two guides to moral and intellectual self-management which we may call ‘the Way of the Will’ and ‘the Way of the Reason.’

The Way of the Will: Children should be taught (a) to distinguish between ‘I want’ and ‘I will.’ (b) That the way to will effectively is to turn our thoughts away from that which we desire but do not will. (c) That the best way to turn our thoughts is to think of, or do some quite different thing, entertaining or interesting. (d) That after a little rest in this way, the will returns to its work with new vigour. (This adjunct of the will is familiar to us as diversion, whose office it is to ease us for a time from will effort that we may ‘will’ again with added power. The use of suggestion as an aid to the will is to be deprecated, as lending to stultify and stereotype character. It would seem that spontaneity is a condition of development, and that human nature needs the discipline of failure as well as of success.)

The great things of life, life itself, are not easy of definition. The Will, we are told, is ‘the sole practical faculty of man.’ But who is to define the Will? We are told again that ‘the Will is the man’; and yet most men go through life without a single definite act of willing. Habit, convention, the customs of the world have done so much for us that we get up, dress, breakfast, follow our morning’s occupations, our later relaxations, without an act of choice. For this much at any rate we know about the will. Its function is to choose, to decide, and there seems to be no doubt that the greater becomes the effort of decision the weaker grows the general will. Opinions are provided for us, we take our principles at second or third hand, our habits are suitable, and convenient, and what more is necessary for a decent and orderly life? But the one achievement possible and necessary for every man is character; and character is as finely wrought metal beaten into shape and beauty by the repeated and accustomed action of will. We who teach should make it clear to ourselves that our aim in education is less conduct than character; conduct may be arrived at, as we have seen, by indirect routes, but it is of value to the world only as it has its source in character.

Every assault upon the flesh and spirit of man is an attack however insidious upon his personality, his will; but a new Armageddon is upon us in so far as that the attack is no longer indirect but is aimed consciously and directly at the will, which is the man; and we shall escape becoming a nation of imbeciles only because there will always be persons of good will amongst us who will resist the general trend. The office of parents and teachers is to turn out such persons of good will; that they should deliberately weaken the moral fibre of their children by suggestion is a very grave offence and a thoughtful examination of the subject should act as a sufficient deterrent. For, let us consider. What we do with the will we describe as voluntary. What we do without the conscious action of will is involuntary. The will has only one mode of action, its function is to ‘choose,’ and with every choice we make we grow in force of character.1

Questions and Thoughts to Consider:

- In modern classrooms, how does atmosphere get contaminated?

- What does Mason say about the difference between I want and I will?

- How do artificial rewards and incentives reinforce in students that which they desire rather than that which they will?

- Talk about the effect that artificial rewards and incentives can have on a student’s capacity for intrinsic motivation and the implications of that.

- How do these attacks on the students’ will affect their character?

- How do we as parents and educators turn out persons of good will?

- What are ways we can influence the children to choose well?

1 Charlotte Mason, Towards a Philosophy of Education, 128-129.