Ambleside Schools International Articles

Browse more Ambleside Schools International Resources.

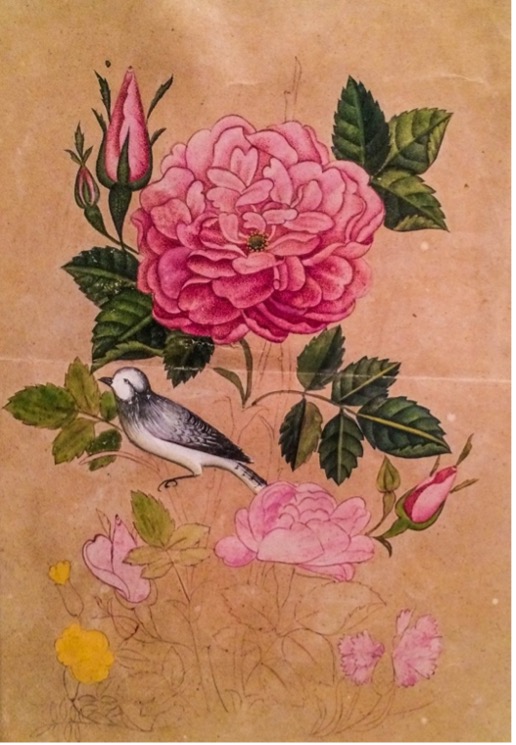

“The Nightingale and the Rose” a tale by Oscar Wilde

The Poet and the Essayist are our Teachers.––A child gets moral notions from the fairy-tales he delights in, as do his elders from tale and verse. So nice a critic as Matthew Arnold tells us that poetry is a criticism of life; so it is, both a criticism and an inspiration; and most of us carry in our minds tags of verse which shape our conduct more than we know;

“Wisdom is ofttimes nearer when we stoop

Than when we soar.” [Wordsworth.]

“The friends thou hast, and their adoption tried,

Grapple them to thy soul with hooks of steel.” [Hamlet.]

A thousand thoughts that burn come to us on the wings of verse; and, conceive how our lives would be impoverished were we to awake one day and find that the Psalms had disappeared from the world and from the thoughts of men! Proverbs, too, the words of the wise king and the sayings of the common folk, come to us as if they were auguries; while the essayists deal with conduct and give much delicate instruction, which reaches us the more surely through the charm of their style.

… Literature is full of teaching, by precept and example, concerning the management of our physical nature.

~ Ourselves, Book 1

In these insightful ideas, Charlotte Mason gives us a thoughtful vision to the significance and purpose of a ‘literature lesson’ to a child’s education. At Ambleside Schools, we believe as she does that ‘a child ‘gets moral notions’ from these stories. When we reflect on the Holy Spirit’s working in our life, we can recall how a word or phrase, or passage may suddenly come to mind at any given time — often at ‘just the right moment.’ Quickly we recognize the voice of our Father in a Bible verse or the lines from a poem or hymn we learned long ago. Imagine when a child’s mind is full of these ‘moral notions’ acquired through attentive reading and listening, narration, and thoughtful discussion from living books. The mind becomes a storehouse of ideas that Holy Spirit may use to speak to and guide us when the time is just right.

Following is a lovely exam narration by an Ambleside Homeschooling 2nd grade student from the poignant story he listened to by Oscar Wilde, “The Nightingale and the Rose” with a note from the mother as she shared this with me. It is worth noting the many accurate details and the use of author’s language in this thorough retelling that demonstrate the child’s habit of attention and depth of engagement with the story and author (Author):

I’m sending this to you because I love that the Idea stuck with him! His sister, Sweet Savannah was weeping as we read this part. What a moving story:

“My roses are red,” said the tree, “as red as the great coral fans that wave beneath the ocean. As red as the sunrise and the sunset. But this winter the frost has chilled my branches and has nipped my leaves and I will bear no roses this year. But there is one way, but it is too terrible that I dare not tell it to you.”

“Tell it to me,” said the Nightingale, “I am not afraid.”

“You must pierce your heart with a rose and sing your sweetest song before the sunrise comes up.”

“That is a terrible price to pay,” said the Nightingale, “but I will do it for the sake of true love. Surely love is a wonderful thing. It cannot be bought in the balance for gold, nor be weighed out like oranges and apples. And you cannot give any gem for it, no matter how beautiful it is.”

And the holm oak tree said, “I will be sad without you, please sing me your sweetest song.”

And she sang her sweetest song for the oak and then went to the rose tree to press her heart against the thorn. So, she sang for a bit and then the flower started forming. The petals were pale.

“Press closer little nightingale,” said the tree, “or dawn will come before it is finished,” and she pressed closer and kept singing.

And a little tinge of crimson appeared on the outside of it. “Press closer, little nightingale, or dawn will come before it is finished!”

So, she kept singing and pressed closer. And she did that and then the time went by ‘til it was all crimson except for the very center, for only the heart’s blood of a nightingale would make the center of the rose fully crimson.

“Oh, do press closer, Nightingale, or dawn will come before it is finished. Because dawn is at the door.”

And she pressed still closer, and the thorn pierced her heart and the blood flowed out and her song became fainter, and her song became wilder for she sang of the love that is perfected by death and the love that dies not in the tomb. And Echo heard it and took it to the shepherds, and it woke them in the fields, and she took it to the green caves under the sea where the nymphs rejoiced.

And finally, the song became fainter and fainter until it stopped, for the Nightingale had died.

“Look Nightingale, the rose is finished!”

But the nightingale did not answer, for she lay dead in the long grass with the thorn in her heart. The rose was crimson on its girdle and crimson in its heart and crimson all over.

The student opened his window and said, “What a piece of luck! This rose is the finest rose in the world. I’m sure the professor’s daughter will dance with me now.”

And he plucked it and brought it to the professor’s daughter and said, “Look I have brought you a red rose and now you will dance with me.”

“No, I will not. The chamberlain’s son has sent me some real jewels and as everyone knows jewels are much more better than flowers.”

“Well, I think you are very rude,” said the student.

“Well,” said the professor’s daughter, “What are you? Just a student. Why I don’t think you even have silver buckles in your shoes like the chamberlain’s son does.”

The student threw the rose into the street and a cartwheel ran over it. And he went into his room and said, “Love is a very silly thing, I think I will go back to philosophy.”

And he picked up a very big and dusty book and began to read.

Shannon Seiberlich

1 Charlotte Mason, A Philosophy of Education, Chapter 2.